TL;TR: Provide your team with structure and positive norms, and productivity and satisfaction will raise. This post is a narrative adaptation of a presentation I have delivered on multiple occasions in various workplace settings.

⌚️ Estimated reading time: 15 min

Table of Contents

What makes a team more productive than others?

Teams productivity is a subject that I find personally fascinating (e.g. “Accept every offer”). Researchers have hypothesized and tested many factors:

- Age

- Tenure

- Strong leadership

- IQ

- Team members sitting together

- Consensus-driven decision making

- Extroversion of team members

- Individual performances

- Team size

- …

What Google found out 1 2 3 was that nothing of that matters, or at least it is not significant. This research, although not groundbreaking, is noteworthy as it originates from a big company rather than an experimental setting. For instance, forty years ago, researcher Meredith Belbin already observed that teams comprised of highly skilled individuals might underperform compared to less skilled counterparts — a phenomenon she named the Apollo Syndrome 4.

And then, what matters? They found one thing mattered more than the others: norms.

But before we see what norms are, a little digression. From my own experience, norms don’t develop within a team without certain foundation: structure. Structure is, in my opinion, the necessary but not sufficient ingredient that allows a group of individuals to discover what are the norms that work for them. In this post I wanted to explain what is structure and norms, and show that “structure plus norms” trump individual qualities and can help growing a happier and more productive team.

Structure

I firmly believe “structure” is not an aspirational or subjective need. It’s embedded in our brain. Our brain is a highly sophisticated engine. It also consumes a lot of energy, especially because it’s engaged in everything we do, no matter how trivial. For example, if we enter a messy room, our brain can feel overwhelmed. It won’t make us immediately feel tired, sad or appalled but it will take a toll on our concentration capacity (although it might boost creativity). Conversely, a tidy room will make us feel better (although it can also bore us or make us less creative).5 6 Not only our brain craves structure: the lack thereof can be detrimental to an organization.

If we are going to talk about structure, we need to talk about Jo Freeman. She is a feminist activist and political scientist with a long history of activism going back to the 60s. She wrote a widely cited article called The Tyranny of Structurelessness7. Freeman recognized that oppression of women is not always limited to interactions between men and women. She observed that a similar oppression was happening, ironically, also within her feminist circles or among groups consisting entirely of women. She hypothesized that there must be other factors that explained said oppression.

For example, she observed that in her feminist circles, there were implicit, unacknowledged and unaccountable structures, non-written rules, cargo cults and non questioning the status quo. The lack of structure was fostering a “tyranny”, to the detriment of the group and its goals. Ironically, again, this oppression was originating from people striving to make a better world. Freeman suggested that introducing more structure to those groups and submitting that structure to a democratic control would make them more effective. However, she also cautioned against swinging to the opposite extreme: adopting a rigid structure.

Freeman also provides a few pointers about how to add structure to a group of people, for example:

- Submit authority in a group to the group.

- Avoid a person holding responsibilities for too long.

- Promote transparency and diffusion of information.

(1) Submitting authority in a group to the group, as Freeman explains, is about distinguishing “authority” from “power” and give the power to the group, delegate, and distributing also authority among as many people as possible.

(2) Avoid a person holding responsibilities for too long, it can allow people to amass power. It’s good to rotate positions and tasks. Follow rational criteria to allocate tasks but consider people’s preferences.

(3) Promote transparency and diffusion of information. Strive for equal access to resources, including skills and information. Information is power, and the farther it reaches, the more the power is distributed.

It’s fascinating to observe the significant overlap between Jo Freeman’s observations from the 70s and the relatively recent findings by Google.

When I first learned8 about “The Tyranny of Structurelessness”, it really rang true to my experience. Not only regarding the structure of teams but also the structure of work. Having regular and fixed rituals (I hate that name!), weekly 1-1s, participating in the planning of tasks, involving and letting people decide most aspects of the functioning of the team, among other things, have proven useful to me. In fact, I cannot claim those things are the optimal way to lead a team, but I’ve observed that teams without those elements are awful to work in.

Norms

As mentioned before, Google found out that teams with strong norms had significant productivity gains:

The researchers eventually concluded that the good teams had succeeded not because of innate qualities of team members, but because of how they treated one another. Put differently, the most successful teams had norms that caused everyone to mesh particularly well.

– C. Duhigg, Smarter, Faster, Better

But let’s hit the dictionary before we show what kind of norms were making Google teams more productive:

Norm (noun): Principle of right action binding upon the members of a group and serving to guide, control, or regulate proper and acceptable behavior.

Norms are guidelines, but not necessarily written ones. The important thing is that they are accepted among the group and they are used by most of the people most of the time. Good norms must bring a positive effect. Certainly, norms can also be negative. For instance, if a leader often interrupts teammates during a conversation, it establishes an “interruption norm”, which might discourage people from speaking up. See also 9 10.

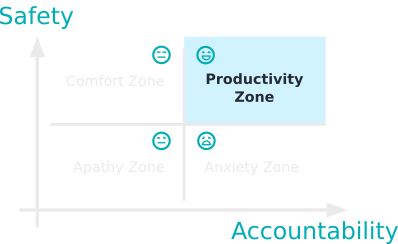

When delving into their extensive data, the researchers discovered that not all the norms were equal. Norms fostering safety and accountability had a greater impact than the rest.

Safety

In the previous example, a leader interrupted teammates frequently. That might discourage people from speaking up. In other words, people will feel less safe to express their opinions because the fear of being interrupted when doing so. Norms that promote safety make the group a better place for taking risks and grow diversity. Taking risks and embracing diversity —whether in terms of people or opinion— is a key ingredient in innovation, and innovation will benefit any group in a competitive setting.

Many norms around safety are about the following topics:

- Avoid embarrassment, rejection, or punishment for speaking up.

- Allow (encourage) mistakes.

- Increase interpersonal trust.

- Cultivate social sensitivity.

To encourage (1) speaking up, acknowledging your own fallibility (e.g. stating you don’t know something), especially from managers, will do wonders. Being curious and a good listener, and allowing everyone to speak, will encourage people to speak up. When people feel comfortable being themselves, they also tend to express themselves more freely. That requires of a lot of mutual respect and accepting the different.

(2) Allowing mistakes is easier if you admit your own mistakes. If something goes wrong, pointing to the causes and solutions instead of the guilty person, will also make people feel more comfortable. Mistakes should be seen as opportunities to learn and improve.

If you let people speak up and allow them to make mistakes, you will (3) increase trust with each other, avoiding “the emperor has no clothes”-kind of situations. Fostering positive and negative feedback will also help there.

Google also found that very productive teams showed (4) high social sensitivity, that is, people have empathy for each other, people worry about each other.

One skill worth learning, which touches upon many of the points above, is active listening:

Active listening is listening on purpose. Active listening is being fully engaged while another person is talking to you. It is listening with the intent to understand the other person fully, rather than listening to respond.

– Active Listening, Wikipedia

Active listening is not a technique but a set of practices, tricks and principles, for example: listen to each other and let (and encourage) everyone to speak. Don’t interrupt each other. Allow and encourage asking questions, especially open-ended ones. When replying to someone, summarize what the person said to show that they are being heard and to make sure they were understood.

Accountability

Let’s hit up the dictionary one more time for this:

Accountability (noun): Obligation or willingness to accept responsibility or to account for one’s actions.

Accountability is more about people taking responsibility rather than having scapegoats for everything. Quite paradoxically, accountability norms are about making accounting unnecessary. If people feel responsible for their fate, they act consequently and accounting is not needed.

A first impression some people have regarding safety and accountability is that there might be some trade-off. That pursuing accountability might be detrimental to safety, or vice versa. The best approach is to aim for both high safety and accountability11 12. Maximizing only one of them can be as unproductive as having neither:

Accountability norms usually revolve around the following topics:

- Overcommunicate.

- Be data and fact driven, result oriented.

- Capitalize on uniqueness and strengths of people.

- Yield control to the team.

- Instill purpose.

(1) Overcommunicating is about sharing the vision, priorities and strategy. Share success, rationalize failure with your team. Be honest and strive for balance. Research also shows that people not only need what to do but also why they are doing things. That is, not only SMART objectives, but also a “stretch objective” that makes sense altogether and reinforces purpose (see Purpose below).

(2) Being data and result driven will remove politics and arbitrary discriminations.

When it comes to (3) capitalizing on uniqueness, from my experience, we often set milestones and performance goals for our teams modelled mostly after our own abilities, preferences, and biases. That is a receipt for failure and will increase your workload as a manager. Rather than seeing your team as a uniform labor force, let them do what they do best and help them with the things they don’t do well yet. For that, it’s crucial to have a diverse team bringing in different skill sets, unless what you do doesn’t require any creativity or it is very narrow in scope.

Empowering your team and (4) giving them the control will increase their motivation and will reverse the power dynamics, accountability won’t be needed. However, most people are not prepared or willing to accept control. You have to create “opportunities to make choices so that people get the sense of autonomy and self-determination” 2. When chores are presented as choices rather than as commands, researchers have found that people are more motivated to complete difficult tasks. This is something people with kids know well: “do you want to wear today your red or your blue scarf?” will work better than “put on the scarf!”. Similarly, when tasks are presented as a “learning exercise”, rather than an activity which can succeed or fail13, people are more likely to engage and perform. Another interesting concept explained in the literature is “bias towards action” 2: by letting people act, even if they make many mistakes in the beginning, will create a safer environment and turn people into responsible individuals.

Purpose

Purpose allows us to answer why we do things, and knowing “why”, in general, motivates people. Purpose is sometimes overlooked with excuses like “work is just work”, “people should be self-motivated and proactive” or “there’s no way I can bring purpose to evil-product-company-or-field”. Purpose is usually considered a tool of accountability. The presentation upon which this post is based had an entire top-level section dedicated to this topic, highlighting its importance. This post didn’t want to be any less.

From my experience purpose norms can be related to:

- Make things real, down to earth.

- Have “moonshots”, “stretch” goals.

- Give agency.

- Making a difference, feeling helpful.

- Learning.

While we can develop a big deal of our trade without talking to users, I’ve observed how some people derive satisfaction seeing their work being used by others, even if the feedback from users or customers wasn’t always positive. This is an example of how (1) making things real, down to earth can create purpose.

(2) Moonshots, named after the famous President Kennedy’s goal of reaching the moon in a decade, is Google’s name for goals with extreme high risk and extreme high impact. (2) Stretch goals are perhaps the moonshot incarnation outside Google. While SMART goals or things like OKRs might work well from an organization and project point of view, they can be boring. Having a “higher order” or challenging goal can motivate people. If not done correctly, it can backfire.

(3) Giving agency is about people having a say on things (e.g. goals, timelines, strategies, technologies, tools).

Similar to making things down to earth, (4) making a difference will also motivate people and fill their work with purpose. (4) Feeling helpful is also something that most people, fundamentally, enjoy. Some companies have norms like spending some fixed time with local charities and similar. If not done well, this can be dangerous and can become superficial altruism. Sometimes it’s easier to be helpful to the closest ones, for example, by teaching something to a teammate.

People have different motivations and goals in life. But one thing common to everyone, and coded in our DNA, is that we enjoy (5) learning something new and improving. It gives us that dopamine reward that we cannot live without. Some companies allow time off for learning or have regular knowledge sessions.

Some norms that worked well for me

I wanted to conclude with a list of some norms which have proven useful to me and that I strive to instill in my teams, with varying degrees of success:

Safety

- Distribute equally conversation turn-taking.

- Praise in public, criticize in private.

- Situational humility12: perhaps not so “situational”, but I admit often how little I know, how many mistakes I make.

- Principle of charity: when interpreting what other people said, I try to select the best possible interpretation for their statement. If there’s not a plausible good interpretation, I ask politely if the interpretation I made is correct.

Accountability

- The person closer to a problem has to be involved in the solution14.

- Encourage the team to act, to have “bias towards action”, as to render myself less necessary and avoid people being idle (which might demotivate or make them feel guilty about the situation).

- Regular knowledge sharing sessions and 1-1.

- Always answer requests, even if it is with “I’ll answer tomorrow” or “I won’t be able to do it because X”. About this one, I cannot be certain it improves accountability, but I can say that people that regularly don’t answer to requests, are awful to work with and accountability with them is very low.

References & Notes

-

What Google Learned From Its Quest to Build the Perfect Team. Duhigg, C. Online article; possibly behind paywall (2016). ↩

-

Smarter faster better: The Transformative Power of Real Productivity. Duhigg, C. Random House Books (2017). ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Re:Work. Google. Something weird happened to this site: as of February 2024, a site only in Japanese has replaced the wonderful original site. Fortunately, long time ago, I scrapped the content and made it available as epub/pdf at https://github.com/daniperez/rework . ↩

-

The Apollo Syndrome. Online article. ↩

-

It’s Not ‘Mess.’ It’s Creativity. Vohs, K. D. Online article; possibly behind paywall but author distributes a pdf in her site. ↩

-

Physical Order Produces Healthy Choices, Generosity, and Conventionality, Whereas Disorder Produces Creativity. Vohs, K. D., Redden, J. P., & Rahinel, R. Psychological Science, 24(9), 1860-1867, (2013). ↩

-

The Tiranny of Structurelessness. Freeman, J. (1970). ↩

-

I learned about “The Tyranny …“ from K. Danielson from Zalando, who exposed the idea in the meetup “Diversity and Inclusion in Open Source”. She made the point that structure in a team can improve inclusion of minorities but it will benefit not only minorities. ↩

-

What Great Managers Do. Buckingham, M. Online article (2005). ↩

-

Decoding Leadership: What Really Matters. Feser, C., Mayol, F. et al. Online article (2015). ↩

-

Building a psychologically safe workplace. Edmondson, A. Youtube, TEDx HGSE (2014). ↩

-

How to turn a group of strangers into a team. Edmondson, A. Youtube, TED NY (2018). ↩ ↩2

-

Jo Freeman concurs, she warns about “sink or swim” methods 7. ↩

-

The person affected by a decision has to be involved in the decision. Reference2 shows the difference between Toyota and General Motors lines of car assembling back in the 80’s. In Toyota’s, anyone could “stop the line” anytime (despite expensive) by means of a chord (andon chord). That was creating safety among workers because they could stop the line when things were not going well, but it was also making them take decisions on the spot to avoid future problems in the cars. ↩